Five Approaches Towards Fostering a Multicultural Church (2/2)

Celebrating our differences and drawing us toward unity in Jesus Christ

This is the second of a two-part contribution to the topic of multicultural churches. See part 1 here.

If you read my previous article, we looked at three benefits of fostering a multicultural church. I believe it is imperative for church leaders and members alike to seriously consider a contextually appropriate way of being a multicultural church.

As mentioned in the last article, Brouwer describes truly multicultural churches as ones that represent an engagement of people from varied nationalities, who still identify with and engage with those cultures to some degree.1 Of course, if people are identifying and engaging with those varied cultures as they gather, this raises big questions about the inevitable tension between diversity and unity between these cultures. Branson and Martínez highlight the crux of our discussion in this article: ‘The question is how to express the new reality of the gospel in ways that both celebrates our differences and draws us toward unity in Jesus Christ.’2 So how do we do it?

FIVE COMMON APPROACHES TOWARDS FOSTERING A MULTICULTURAL CHURCH

We will consider five approaches that churches typically pursue to achieve this multicultural vision. A multicultural church will aim to both celebrate cultural diversity while also expressing unity in Christ. Some ministry approaches fare much better than others when pursuing this goal. Broadly speaking, churches will either hold distinct worship gatherings catering to different cultural groups, or they will attempt to integrate different cultures within the one worship gathering. The first category prioritises diversity, the second prioritises unity.3 I’ve created a diagram to summarise how these five approaches relate to one another:

We will discuss these approaches in the order below, but feel free to click on one to jump straight to it:

iii. Monocultural Assimilation

iv. Multicultural ‘Variety Show’

Which is the best approach? As we will see, I believe that a genuine multicultural expression of church is possible regardless of whether your worship gatherings are distinct or combined. Both have strengths, however, neither is without challenges either. These challenges can certainly be mitigated to some extent by wise leadership. And adequate consideration of your context and congregation size is vital for determining the best way forward.

A. DISTINCT GATHERINGS

These first two approaches tackle the challenge of creating a multicultural church by offering two (or more) distinct services to cater for people from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. A ‘distinct gatherings’ model prioritises cultural diversity and excels at offering culturally sensitive expressions of Christianity. However, as we will see, adequately accentuating the unity between these diverse cultures inevitably becomes a challenge.

i. Monocultural ‘Silos'

The monocultural silos church model will typically have at least two ethnically distinct congregations—say, an Anglo-Australian and a Chinese congregation—usually divided according to language. In some instances, an ethnic subculture may be ‘planted’ from within the dominant congregation’s culture. Usually though, a new cultural demographic and congregation is taken on by the original congregation and allowed use of their facility—often relating as ‘tenants’ to the larger ‘landlord’ congregation.4 These congregations will often have their own distinct leadership structures and usually gather at different times to one another so that the same facility can be used for each. (While not the focus of this article, many churches tend to ‘silo’ their generational ministries in ways not dissimilar to this cultural approach—here’s my take on multigenerational ministry)

The Homogeneous Unit Principle

The sentiment of this approach follows the ‘Homogeneous Unit Principle’ (HUP) developed by Allen, McGavran, and Wagner. The underlying assumption of this principle is that ‘people prefer to become Christians without crossing racial, linguistic or class barriers.’5 Therefore, it is suggested that culturally siloed churches encourage growth since people of all cultures are the most responsive to the gospel in homogenous contexts.6

For all of its tidiness, I find the ideology of HUP as a model for multicultural churches unpersuasive. Evidence suggests that while isolating homogeneous congregations may lead to church growth, it is certainly not the only approach for doing so.7 Furthermore, these churches face significant challenges when seeking to accommodate second-generation members of these ethnic subcultures. Consider, for instance, where an Australian-born child of Chinese migrants may best be integrated in the life of a monoculturally siloed church. Perhaps most importantly, HUP fails to capture the biblical vision for the church, which is frequently depicted as breaking down homogeneous units of race and class (Romans 15:7–13; Ephesians 2:13–22).

Reflection

So, is a monocultural silos approach the best way to be a multicultural church? A culturally siloed church may experience growth in attendance, at least initially. On the surface, cultural diversity is occurring within the church and this is often celebrated as multiculturalism. However, the power imbalance that typically exists between the cultures and the lack of intentional interaction and learning between the cultures, creates something resembling ‘cultural pluralism’, ‘siloed cultures’, or even, in Whitesel’s words, ‘cultural apartheid’.8 In Oritz’s view:

This model is presented by denominations as a multiethnic congregation, but in reality the relationships [between cultures] are not stable and never go beyond the renting stage to achieve mutual accountability. Therefore, this cannot be considered a multiethnic congregation.9

While short-term church growth is to be celebrated, it must not come at the cost of pursuing healthy ‘race relations and to racial and ethnic reconciliation in the Christian community’, mutual edification being one of the main benefits of multicultural churches.10

ii. Multicultural Partnership

Fortunately, this siloed multicultural model can be improved. Rather than conceiving of a multicongregational church as isolated silos relating to each other in asymmetrically power balanced ways, a far more advantageous approach is for a church to view these cultural communities as partners in the gospel. Whitesel terms this approach as a ‘Multicultural Alliance Church’, which is ‘a heterogeneous organization led by an inclusive and balanced alliance drawing from the different cultures it is reaching. The alliance honors cultural differences by embracing multiple, culturally different worship services that are led by a heterogeneous organization.’11

A multicultural partnership is seen and operates as ‘one church’, comprised of two or more cultural congregations. The pastoral leaders for each congregation form the united multicultural leadership team for the church and share equal stake in evangelism, vision and resources.12 For Whitesel, ‘A strong respect and appreciation of cultural differences often results when leaders are forced to work together to run a church.’13 Accordingly, for members of these cultural congregations, their experience as part of a ‘multicultural’ church can be genuine as the congregations move towards ‘celebration’ or ‘integrative’ models, where autonomous congregations are united by a shared vision, ownership, and regular celebrative fellowship, hospitality, and focussed ministries.14 ‘Worship is still separate, but with combined services on a regular basis. Leaders of the congregations see themselves as one team. Interaction across services happens at all levels.’15

St Thomas’ Anglican Church in Burwood presents itself as an example of a multicultural partnership church. Their website describes themselves as ‘one church with four diverse congregations that meet on Sundays… Ministering to congregations of every age with English, Cantonese and Mandarin language services.’ The diversity of their ordained and lay leadership reflects this multicultural partnership.

Reflection

The multicultural partnership approach is certainly an improvement over the ‘monocultural silos’ expression of this distinct gatherings category. Interaction is ensured and imbalances of leadership power can be mitigated. Orriz and Yang believe that ongoing engagement with second generation migrants is aided by having a multicongregational church like this, since these younger people can easily transition to an English-speaking service at the same location—ideally at the same time also—as they feel comfortable, without undermining the unity of the church as a whole.16

In terms of challenges, even with a united leadership, the partnership approach still creates culturally isolated congregations since language differences will almost always create these demarcations. From a pragmatic perspective, for this partnership model to function well, churches will need to have sufficient facilities and leadership to run parallel gatherings. This may not be possible for small churches. In her studies, Yang provides helpful practical guidance for when such a multicultural partnership approach may be winsome:

The Partnership model works more effectively when the English-speaking and NESB [Non-English Speaking Background] congregations are of similar size and have a shared vision.17

While ‘distinct gatherings’ approaches inescapably emphasise diversity over unity, a genuine multicultural church can exist within this framework, provided there is careful consideration of the context and congregation size, as well as a commitment to partnership and regular intercultural interaction.

B. COMBINED GATHERING

The next three approaches tackle the challenge of creating a multicultural church by attempting to integrate people from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds within the one worship gathering. A ‘combined gathering’ model prioritises unity as all members are physically present together. However, as we will see, the extent in which members’ diverse cultural backgrounds can be sincerely expressed and experienced inevitably becomes a challenge for combined gatherings.

iii. Monocultural Assimilation

It is quite normal for the dominant ethnic culture present in a church to define the cultural expression for that church—which in the Australian context typically represents an Anglo-Australian church. The result is that any cultural minorities who may join that community are expected to conform to and assimilate into the prevailing culture’s expression of church.18 As Whitesel rightly remarks, this ‘model is not actually multicultural but is listed here because of prevalence.’19 By and large, most churches in Australia are close to this model.20 (And I would suggest that many non-English-speaking monoethnic churches would fall into this category too)

Reflection

In one sense, I appreciate that this approach honestly questions whether the gospel even needs to be ‘marketed’ to a diverse audience at all; since the gospel rightly transcends all cultures.21 It taps into a ‘Christianised’ build-it-and-they-will-come adage: Preach the gospel, and people of all backgrounds will come to our church. There is a genuine desire to bring the gospel to other cultures. However, such a sentiment fails to recognise that Anglo-Australian expressions of the gospel and the church are just as enculturated as any other representation.22 For example, Anglo churches tend to favour individualism over collectivism. Freedom over duty. ‘Suffering’ in the New Testament tends to be conflated with what Western society understands suffering to be. Even the fact that the sermons and worship are communicated in English is a culturally-motivated decision. Yang offers a cutting rebuke:

Many within the dominant culture are unaware of other cultural patterns. They assume that their Anglo-Australian Christian culture is the norm and that people from other cultures will be assimilated into their culture. They have dominance and power, and may assume they will retain it, not expecting minority groups to have a voice or have an impact on the direction and views of their children.23

The flaw of this approach to multicultural praxis is that it springs from an unhealthy ethnocentrism exhibited by the dominant culture. Certainly, the church may likely still attract some members from ethnically diverse backgrounds, however the prevalence of Anglo-Australian culture results in minimal effort made by members of that dominant culture to understand the cultural contexts of others.24 In its pursuit of assimilating subcultures into the prevailing one, this model creates a truncated expression of the biblical church, fails to capture God’s vision for his people, and prohibits the mutual edification which takes place in truly multicultural environments.25 There must be a better approach than this.

iv. Multicultural ‘Variety Show’

If our first two models sought to maintain cultural integrity by separating cultural groups, this fourth approach does precisely the opposite: unique cultures are combined to form a single, united congregation. This multicultural approach is sometimes referred to ‘melting pot theory’, as it implies that ‘any new ethnic group becomes completely assimilated as the cultures meld together to form a new dominant culture.’26 In practice, this tends to look like a ‘blended culture’, where variety and diversity is celebrated by ‘sprinkling’ cultural relics from all contributing ethnicities into one united spiritual experience.27 It is not uncommon to experience a variety of international musical styles within one service, coupled with distinctive cultural spiritual practices and languages. The Thy Kingdom Come service I attended at St Paul’s Cathedral several years ago is an example of this multicultural approach.28

Reflection

This approach certainly may address the challenges with unity identified by other models. However, unless diligence and care is employed by the leadership team, the resulting experience may be at risk of feeling like a farcical cultural ‘variety show’, where each cultural expression is followed by the next ‘act’. As a combined experience, Whitesel observes that this style can feel like ‘a less than appetizing concoction’, mainly because the resultant blended culture is unnatural for all participants.29 In Yang’s words: ‘everybody, to some degree, feels they are an outsider.’30 The challenge of a blended model like this lies in determining the extent to which people’s input cultures can be respectfully represented, rather than being patronisingly diluted to the extent of tokenistic stereotypes. Taylor’s sentiments are apt:

[W]e don’t want the ecumenical cooks to throw all the cultural traditions on which they can lay their hands into one bowl and stir them to a hash of indeterminate colour.31

Additionally, it is questionable under this blended approach whether cultural barriers and division are actually traversed at all, since the culture ‘variety show’ acts remain stratified, and do not interrelate in any meaningful sense.

v. Intercultural Community

Fortunately, this multicultural approach can be improved. Branson and Martínez believe this blended approach excels when the focus is on Christians pursuing ‘cultural boundary crossing with neighbors and intercultural life within their congregations.’32 This model sees a church as a united congregation, though comprised of people from varied ethnic backgrounds. Where this differs from the ‘variety show’ blended model, is that genuine interrelationship between cultures is paramount, with a commitment to multiethnic leadership, contextualised worship and preaching, and culturally diverse influences over the life and ministry of the church.33 Worshippers embody a willingness to integrate and learn from other cultures.34 Through pursuing an intercultural expression of church, members will experience growth and enrichment, as genuine cultural relationships create an environment of ‘desire to learn from each other’.35

Brunswick Baptist Church presents itself as a sustainable example of such an intercultural church. They write on their website:

[O]ur congregation is now made up of many cultures, backgrounds, ages, and languages, reflecting the vibrancy and diversity of our surrounding suburb. We believe that we can come to know God through this diversity, and by wrestling together with scripture and the Christian tradition, with respect, reverence, and questioning.36

Reflection

I recall a recent experience in my own multicultural Bible study group. We were studying Deuteronomy 18:9–14, in which God speaks out about witchcraft, mediums and the occult. As an Anglo-Australian myself, I found it enlightening and beneficial hearing reflections from members of the group who grew up in non-Western cultures where these practices were commonplace. Having this shared learning enabled me and the wider group to better connect with Scripture and understand its meaning.

On this theme of cross-cultural learning, Michael Bird goes to pains to explain that the Bible is not a book ‘written to us, nor was it written about us’, meaning any encounter with the biblical text involves entering a ‘historically and culturally distant world’.37 Through a commitment to intercultural life, Christians are better equipped to understand their own cultural biases towards Scripture, and will learn insights and applications which better reflect the diversity of the global church.38 Insights into the Bible and the gospel are to be welcomed through different cultural perspectives, with the expectation of mutual enrichment in faith and community, and without diminishing the distinctives of someone’s native culture.

The challenge of syncretism

Yang rightly acknowledges that while this intercultural model can be exciting, it is also the most complex and challenging to maintain.39 When pursuing a vision of an integrated intercultural community like this, problems may arise when differences in cultural expressions of worship simply make worship unconducive or prohibitive for another culture. Lingenfelter and Mayers emphasise this issue by illustrating the irreconcilable differences between a mainstream American Evangelical Mega-church presentation of ‘worship’ and a Saudi Arabian Muslim.40

The inherent tendency toward syncretism in this multicultural model will also reach a point where the differences in cultural expressions create challenges to unity with the historic catholic church, both in areas of orthodoxy and orthopraxy.

In summary, the ‘intercultural community’ is a vast improvement over the ‘cultural variety show’ expression of this approach. However, even though a genuine multicultural church can exist within this framework, when multicultural unity is pursued, diversity and genuine expressions of cultural worship will become more challenging. In her studies, Yang provides helpful practical guidance for when such a multicultural approach may be winsome:

The Integrated model… can work effectively when there are lots of small groups of people from many different communities.41 This model, however, may be less suited to big churches, or the Anglo-Australian churches without NESB [Non-English Speaking Background] people, or to a large NESB group in an Australian church.42

C. OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Near the start of my previous article I said that with this vision of a multicultural church ‘comes much to ponder and many complexities to navigate.’ It particularly raises important questions about the tension between unity and cultural diversity. As we have examined these five approaches, I trust you appreciate these challenges that we face. As we consider potential ways forward, here are a few other complexities to navigate with your church context.

i. The challenge of language

Language is probably the most significant cultural barrier to overcome.43 Ortiz concedes that ‘Language, more than anything else, seems to be what keeps congregations separated. There are certainly cultural issues, but language is what most churches indicated are the dividing line.’44

Even the Apostle Paul recognises the barriers to complete participation if language prevents content from being knowable to another:

‘Otherwise when you are praising God in the Spirit, how can someone else, who is now put in the position of an inquirer, say “Amen” to your thanksgiving, since they do not know what you are saying? You are giving thanks well enough, but no one else is edified.’ (1 Corinthians 14:16–17)

One can easily imagine the difficulty of genuine multicultural participation in church meetings, if each sub-culture is appealing to terminology and language alien to the remainder of the group.45 These challenges can certainly be overcome with respectful listening, questioning, humility, and a willingness to learn another language, though these require additional patience and energy to work through.

ii. The paradox of language

Differences in language certainly create practical challenges to unity. However, it might be surprising to learn that creating distinctions based on language, while a barrier to practical unity, is not treated in the New Testament in the same way as barriers of race and class (Galatians 3:26–29; Ephesians 2:11–16; Colossians 3:11). The biblical translatability of the Christian faith means that Christianity embraces all languages, effectively affirming: You can be a genuine disciple of Christ in your own language and culture. The message of the gospel and its obedience is translatable into other languages and cultures. You can be a genuine follower of Jesus as an Arabic, English, or Hindi speaking person, and in countries where these languages are widespread.46 This is precisely the issue at stake in the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:1–35), where attempts to ‘assimilate Gentile Christianity into Judaism’ is challenged.47 While we are called to break down barriers of race, class, and gender, almost paradoxically, Christians have a right to be able to worship Christ in their own language, and in their own culture.

At Deep Creek Anglican Church, the ministry team were met with the challenge of running an English-speaking service, with an increasing cohort of Farsi-speaking people joining the congregation. They had a loving desire to welcome the participation of people who found English difficult to comprehend. Their solution was to invest in Farsi-speaking ministers who were able to offer live, in-ear translation of the English service into Farsi, and on-screen Bible readings displayed parallel in Farsi, which enables people from different cultures and languages to gather in the one space and worship together in their native tongue. Alongside this, a Farsi Bible study group was offered, which provided further means of integrating non-English speakers into the ministry of the church.

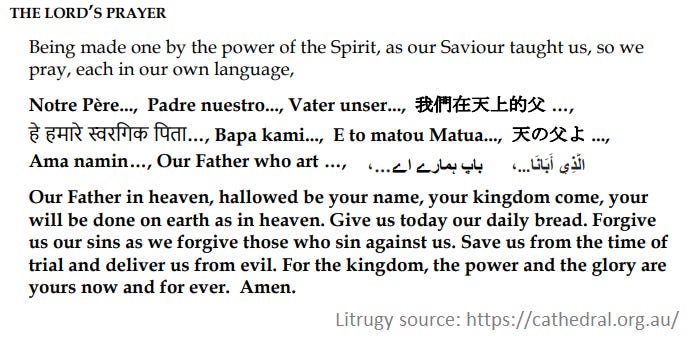

For denominations where written liturgy informs their worship, one effective way of affirming this balance is by enabling members to pray and speak the same liturgy as others, but in their native tongue. St Paul’s Anglican Cathedral uses this approach for items, such as the Lord’s Prayer:

For congregations with linguistically diverse members, another way forward may be to foster a culture of language-specific small groups which meet during week, in addition to the one united, gathered worship service.

iii. The challenge of contextualisation

But language is not the only cultural barrier to navigate. For Sam Chan, the task of uniting cultures under the truth of the gospel is even more complex than mere comprehension of varied language: it requires a conscientious engagement with a contextualised gospel for each culture.48 Christianity is not tied to a particular nation or culture in the way that some other religions tend to be.

And so, without adequate contextualisation of the message, churches will tend to fall into either syncretism or colonialism as they seek to communicate the gospel cross-culturally. Effective cultural contextualisation, then, means that churches have both entered and challenged other cultures with the gospel, resulting in imperatives of gospel obedience and expression that are culturally appropriate for that community.49 This is another massive topic, which I’ll need to write about in the future! I mention it here simply because it needs to be a consideration when accommodating and reaching people from other cultures with the gospel.

Over to you!

Well, with all of this under our belts, it is my hope that our churches will grow to foster a multicultural identity, and that members and leaders alike will explore contextually appropriate ways of doing this in your community. May God bless you as you seek his wisdom.

‘There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.’ (Galatians 3:28)

Douglas J. Brouwer, How to Become a Multicultural Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017), 6–7.

Mark Lau Branson and Juan Francisco Martínez, Churches, Cultures & Leadership: A Practical Theology of Congregations and Ethnicities, eBook. (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2011), 19, emphasis mine.

Of course, there’s nothing to say that your church can’t have a blend of both present either!

Manuel Ortiz, One New People: Models for Developing a Multiethnic Church (Downers Grove: IVP, 1996), 68.

Donald A. McGavran, Understanding Church Growth, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 223.

Peter C. Wagner, Church Planting for a Greater Harvest (California: Regal Books, 1990), 67; Meewon Yang, ‘Ways of Being a Multicultural Church: An Evaluation of Multicultural Church Models in the Baptist Union of Victoria’ (MCD University of Divinity, 2012), 23, https://repository.divinity.edu.au/divinityserver/api/core/bitstreams/0c8c82ed-5ea0-4254-8eed-fb4275248119/content.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 24.

Bob Whitesel, ‘Eight Steps to Transitioning to One of Five Models of a Multicultural Church’, Great Commission Research Journal.8 no 2 Winter (2017): 216; Ian S. Markham and Oran E. Warder, An Introduction to Ministry: A Primer for Renewed Life and Leadership in Mainline Protestant Congregations, eBook. (Malden: Wiley, 2016), 38.

Ortiz, One New People, 67.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 24; Ortiz, One New People, 45.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 217.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 217; Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 26.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 217.

Ortiz, One New People, 66–85.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 26.

Ortiz, One New People, 76; Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 26.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 112.

Branson and Martínez, Churches, Cultures & Leadership, 89; Markham and Warder, An Introduction to Ministry, 38.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 214.

Jeffrey P. Greenman, ‘15. Learning and Teaching Global Theologies’, in Global Theology in Evangelical Perspective: Exploring the Contextual Nature of Theology and Mission, ed. Jeffrey P. Greenman and Gene L. Green (IVP, 2012), 242.

Tracey M. Lewis-Giggetts, The Integrated Church: Authentic Multicultural Ministry, eBook. (Kansas City: Beacon Hill Press, 2011), 17.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 10.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 10.

Matthew D. Kim, Preaching with Cultural Intelligence: Understanding the People Who Hear Our Sermons (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017), 97.

Whitesel writes: ‘The loss of indigenous arts, histories, and traditions creates a world less rich in variety and complexity than God designed.’ See Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 215.

Markham and Warder, An Introduction to Ministry, 38.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 216.

St Paul’s Cathedral Melbourne, ‘Thy Kingdom Come 2019 Beacon Event: Multicultural Service (Order of Service)’, 8 June 2019, https://cathedral.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/beacon-event-print-final-print.pdf; Video of the service can be found at St Paul’s Cathedral Melbourne - Thy Kingdom Come 2019 Beacon Event, 2019.

Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 216.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 122.

J. V. Taylor, ‘Cultural Ecumenism’, Church Missionary Society Newsletter, November 1974, 3; Quoted in Whitesel, ‘Models of a Multicultural Church’, 216.

Branson and Martínez, Churches, Cultures & Leadership, 89.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 27; Ortiz, One New People, 88–90; Jeannie Mok and Ngar Fei Leong, The Technicolour Faith: Building a Dynamic Multicultural Church (Brisbane: Asian Pacific Institute, 2004), 43.

Mok and Leong, The Technicolour Faith, 43.

For quotation see Ortiz, One New People, 76; See also Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 22; Mok and Leong, The Technicolour Faith, 40–45.

Brunswick Baptist Church, ‘Our Story’, Brunswick Baptist Church, September 2021, https://www.brunswickbaptistchurch.org.au/about.

Michael F Bird, Seven Things I Wish Christians Knew About the Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2021), 96, italics original.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 114.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 27–28.

Sherwood G. Lingenfelter and Marvin K. Mayers, Ministering Cross-Culturally: A Model for Effective Personal Relationships, Kindle Edition, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), 4.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 112.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 121.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 23.

Ortiz, One New People, 65.

Yang, ‘Being a Multicultural Church’, 119.

This affirmation based on lecture and in-class discussions in Ridley College’s EM018 MCDC Week 9: ‘Missiological Principles for Multicultural Ministry’.

David Peterson, The Acts of the Apostles, PNTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 418.

Sam Chan, Evangelism in a Skeptical World: How to Make the Unbelievable News about Jesus More Believable (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 138–155; See also Bird, Seven Things, 96–98.

Chan, Evangelism, 149.